Unserved food need not be thrown away

You’ve probably been here before: Your event is under way, and despite the large amounts of food set out, there is far more mingling than eating going on, which is great but the pounds of food left over won’t be. For hotel and event operations, this management of potential post-meeting food waste is a big deal.

Outside of events, you may say it’s an even bigger deal. According to the United Nations, the United States wastes an estimated 133 billion pounds of food per year—roughly 236 pounds per person—and about 1.3 billion pounds of food is wasted globally. Food waste is the one of the largest contributors to the landfill, making up 24% of it. The same waste stream ration applies in the hotel world, as well.

“Food waste is the single largest material that we divert,” says Brittany Price, director of sustainable operations for MGM Resorts International, adding that it is among the 30 different materials that the organization tracks.

Price says MGM focuses on food waste management by adhering to the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) food recovery hierarchy, which lists the best ways to recover food, from most to least preferred, beginning with source reduction, followed by feeding those in need; feeding animals; industrial uses, such as converting food waste, oils and fats into biofuel; composting; and lastly, but hopefully not, sending it to the landfill.

Although food waste at events is just a small piece of the global food waste pie, there’s no reason to think event professionals and the properties in which they gather can’t come together to make the world just a little less wasteful. Many venues and hoteliers around the United States are tackling this issue as you read these words. Keep reading to find out how it’s being done.

Reducing the Source

Like the EPA’s hierarchy illustrates, source reduction is exactly where MGM begins. Price agrees that source reduction, not creating food waste in the first place, is the ideal.

Price and her team focus on ways to prevent more food than necessary finding its way into the ballroom. “How do we [create the] right size portions for our restaurants, for our banquet and convention attendees?” she asks. “Often times, people’s mind are bigger than their stomachs and they fill up a large plate because there’s space to fill.”

Read More: Food Rescue and Donating to Those in Need: The Law Is On Your Side

She says they also work with convention clients on menu planning and offer certain items on specific days so they can bulk order more efficiently and have less waste by creating the same meal for multiple clients.

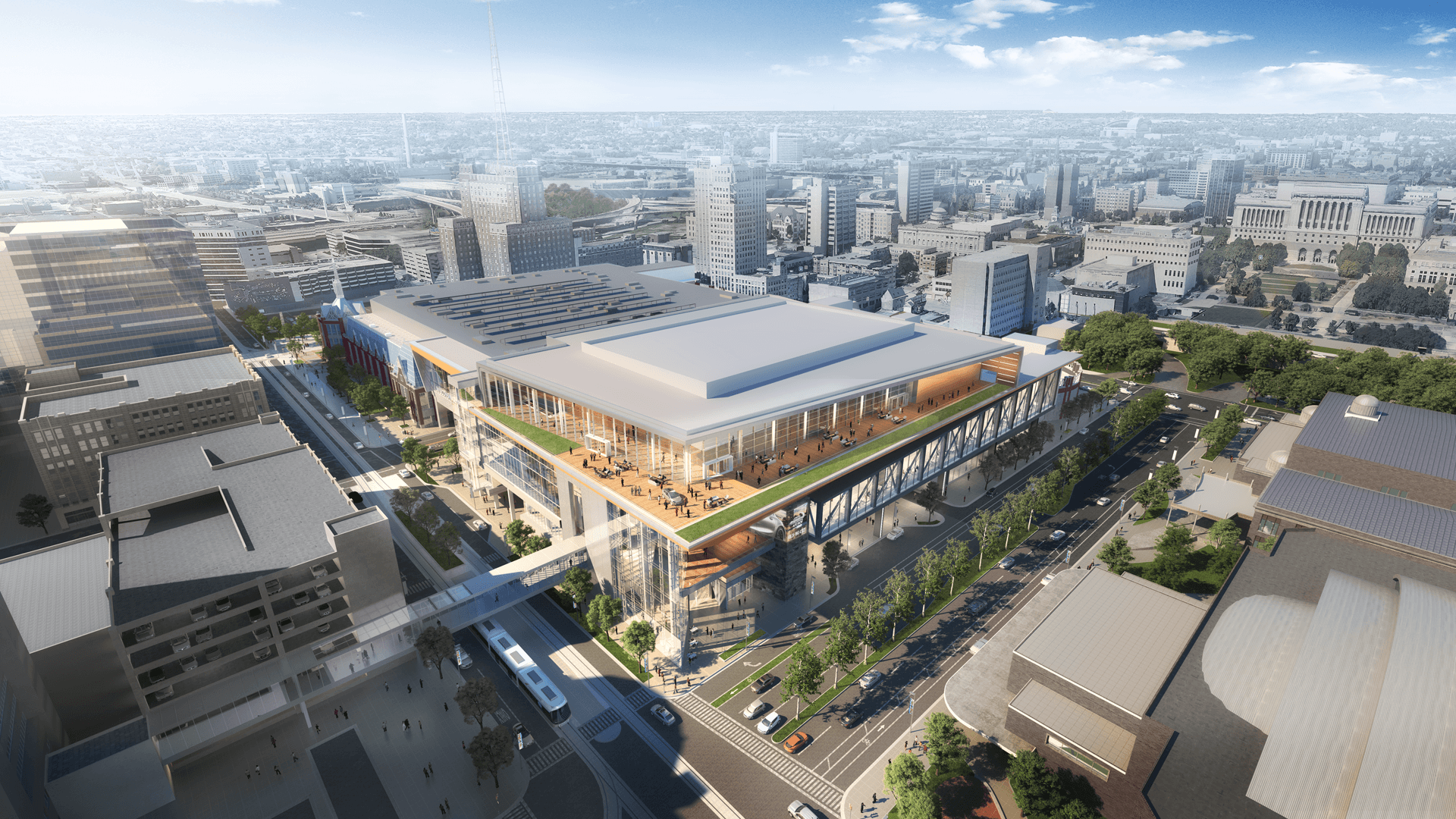

Over in Milwaukee’s Wisconsin Center District (WCD), one of their methods of food waste prevention could arguably be on the riskier side. The practice is what Chris Pulling, executive chef for Levy Restaurants, the exclusive F&B provider for WCD, and his team call “just-in-time” cooking, which they began doing over the last year-and-a-half.

“We find that our timing has been pretty good, and because of that, we’re not throwing a lot of things away at the end of the night,” Pulling says. “That’s one way of beating the prices.”

He says sometimes with just-in-time cooking you are taking a chance because the line may be moving faster than you think, but they’ve done it often enough that they’re confident in their ability to operate successfully. They also do homework on incoming groups, asking questions about the ways a group may take breaks, if they’re coming as a whole or in a more staggered flow. “Not only does this help us with our cost, but it also helps with the quality because they’re getting something that just came out of a tilt skillet,” he says.

Levy Restaurants also shares historical group information among the 31 venues in its convention center division through Smartsheet, which includes convention centers like Austin Convention Center, Oregon Convention Center and Puerto Rice Convention Center. So, if a group is getting together at Oregon Convention Center (OCC), for instance, OCC can go into that digital sheet, see what foods groups liked most and least at WCD and operate from a more knowledgeable place and create less waste in the process.

“Not only does [just-in-time cooking] help us with our cost, but it also helps with the quality…”

– Chris Pulling, executive chef, Wisconsin Center District

“I think we’re doing a fabulous job of sharing ideas, what worked, what didn’t work, because the last thing you want to do is create something really special and it’s not what they want, so at least with this data we can do a little more research,” Pulling says. “We try to think of everything we can to reduce the amount of production and if we can do that or do it just-in-time as much as possible, then we are certainly cutting down on waste.”

Giving to the Community

“Even with the best planning, there’s going to be food that goes unserved.” Price says. “So, the next best thing you can do is give food to the community.”

In 2016, MGM partnered with Three Square, a southern Nevada food bank, and since then, the collaboration has resulted in the donation of 3.5 million meals to the community through a mix of their donation program and cash-funded meals—Three Square itself donates about 50 million meals annually. In addition to donating perishable foods from the event, they also donate nonperishables from locations like the minibar or in MGM’s retail stores, as well as other nonperishables that aren’t going out to the floor for any number of reasons.

Although MGM has been focused on donating food since around 2007, it wasn’t until nine years later that the partnership with Three Square began, created with the intent to focus on rescuing food from events. “That took time and investment to learn how to do it safely,” Price says. The partnership included a $768,000 grant to develop the infrastructure and appropriate equipment to donate food responsibly.

“Even with the best planning, there’s going to be food that goes unserved. So, the next best thing you can do is give food to the community.”

– Brittany Price, director of sustainable operations, MGM Resorts International

Additionally, MGM gets it employees involved in food recovery, encouraging them to appropriately discard food through signage stationed at trash cans in the properties’ employee lunchrooms, so it can later be sent in the right direction.

Food Safety and Healthy Hogs

While food is in limbo—after it’s cooked but before food it’s served to groups—it lives in hot boxes, portable ovens used to move food around while keeping it hot enough to serve. “After an event, if food is untouched or unserved and still maintained in the hot box, we can go in and make sure the food stays above a hot-holding temperature of 135 degrees. If it is, then it’s safe for us to donate.”

From there, the food is placed in disposable pans and frozen in glass chillers—what Price calls “the convection oven of freezers”—stored, and once there is enough in the warehouse, it is then sent off to Three Square. Different nonprofits can then order that food from Three Square to serve to the wider community.

“The thing about donating a prepared food product is ensuring it’s done safely and that’s really where we developed a program around freezing the food to safely preserve it and get it back into the community because we want to be able to donate safe, nutritious food,” she says. “We don’t want anyone to get sick, so managing it and putting those proper health and safety parameters were a must for us.”

Read More: Sustainable Meetings Through Renewable Concepts

Because the program wants to serve food with safety in mind, only a small percentage of food actually makes it to the donation process. Once it’s out of the hot box or glass chiller, it is no longer considered a safe food item. “Once it’s out on the buffet line, it’s exposed to all the elements and no longer recoverable,” Price says.

This is where the next form of food waste recycling comes in: feeding livestock. MGM has two pig farm partners in Las Vegas with whom they share the hotels’ food scraps to feed the livestock. Food is placed in large unlined yellow bins—unlined because they want to ensure no plastic is mixed in with food—then taken out to the dock, where it awaits its final destination.

While Nevada allows food scraps to be given to animals, food donation for animals varies by state. Some U.S. states have regulations such as not allowing “animal-derived waste,” like meat and eggs, or vegetables, to be fed to animals, including Illinois and Mississippi—both of which don’t allow either—according to Leftovers for Livestock: A Legal Guide for Using Food Scraps as Animal Feed, a guide on federal laws for using scraps in animal feed, created by Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic, Food Recovery Project and the University of Arkansas.

Turning Waste to Proverbial Wine

Food waste recycling goes beyond just food. It includes oils, as well. “We’re able to take our fats, oils and greases, collect those and turn them into biofuels,” Price says. MGM partners with operators who refine those forms of waste and turn them into different energy sources. For example, yellow grease, used for frying food in the kitchen, is given to one of its collaborators after use, refined, sold and used as energy. Brown grease, the chunky leftovers you may see left in a grease trap, is removed, and water is extracted, which is then turned into a biofuel.

Food waste recycling goes beyond just food. It includes oils, as well. “We’re able to take our fats, oils and greases, collect those and turn them into biofuels,” Price says. MGM partners with operators who refine those forms of waste and turn them into different energy sources. For example, yellow grease, used for frying food in the kitchen, is given to one of its collaborators after use, refined, sold and used as energy. Brown grease, the chunky leftovers you may see left in a grease trap, is removed, and water is extracted, which is then turned into a biofuel.

The last operation, before sending food to the landfill, is composting. MGM partners with two composting companies that take food waste and compostable disposables, like paper cups and bamboo plates and utensils, to make compost fertilizer.

“We look at all these methods as a means to divert our food waste, with the very last thing being the landfill,” Price says. “We really want to prioritize, optimize and focus on source reduction as the primary [method], and we have all those other outlets to be able to responsibly manage food waste.”

When WC expands in 2024, the facility will be offering more than an expansion to 300,000 sq. ft. of space. The facility will begin using the Orca, a food waste technology that prevents food from having to go to the landfill. It does this by taking the organic material fed into it and turning it into liquid that can then be used in the facility’s sanitation infrastructure.

Pulling says he and Julio Henriquez, general manager of Levy Restaurants’ in-house staff, advocated for the Orca when plans for Wisconsin Center’s expansion were coming to an end. “We wanted to be the first convention center in Wisconsin to have this type of system in place.”

Another item Pulling says WCD will have soon is a freeze dryer, so if they ever have extra food, like fruits for instance, they’ll be able to freeze dry, pulverize and use them for different meals, like a mousse or a smoothie.

“You can freeze dry so many different things, it’s amazing,” he says. “I’m excited about that one because we [make] a lot of desserts. Rather than throw those berries away because they’re starting to turn, you can catch them before and freeze dry them. They last for 25 years once they’re freeze dried, it’s kind of a cool thing.”

Rock and Wrap it Up!

Rock and Wrap it Up! (RWU), an anti-poverty think tank, has been in operation for nearly 30 years and partners with a handful of different venues, hotel brands and organizations. What began as a partnership with bands and musicians, such as Aerosmith, The Rolling Stones and Bon Jovi, to donate untouched but prepared food to the hungry turned into an operation that also collaborated with sports franchises in the NFL, NBA, MLB, MSL, NASCAR venues and the entire NHL; music venues, such as Jones Beach Concert Theater; five hospitals, including Yale New Haven Medical Center; and more than 200 U.S. schools.

RWU began its Hotel Wrap! Program in 2008 with The Langham Hotel in Pasadena, California, which donated food from its corporate events, which RWU then passed on to local organizations. In 2009, RWU partnered with New York Marriott Marquis, which donated vanity items like toilet paper, tissue boxes, shampoos and conditioners and other items that would have been thrown away after guests check out.

Today, RWU partners with hundreds of hotels and conference centers, with brands like Marriott International and Hyatt Hotels, connecting them anti-poverty organizations and agencies. In most cases, Syd Mandelbaum, founder and CEO of RWU, says, they provide hotels with information on local agencies and they reach out to them themselves.

“This is all about getting assets to agencies to fight poverty,” Mandelbaum says. “That has been the elegance of Rock and Wrap it Up!, so many of our partnerships are lifetime partnerships.”

Food Waste Prevention Resources

As of 2018, only 32% of that roughly 133 billion pounds of the aforementioned food was diverted to “animal feed, bio-based materials/biochemical processing, codigestion/anaerobic digestion, composting, donation, land application and sewer/wastewater treatment,” according to the EPA.

Before this, in September 2015, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the EPA announced the domestic goal to reduce food loss and waste by half by 2030. Today, more than 45 organizations, including grocery stores, food producers and retail outlets, including Albertsons, General Mills, MGM Resorts, Starbucks, have answered the call to reduce food waste.

Additionally, the EPA provides a list of state and local environmental agencies and waste management programs in the U.S., titled “Regional Resources to Reduce and Divert Wasted Food Across the United States,” that provide resources and information about food recovery, food donation, composting and more.

This article appears in the digital-only May 2023 issue. You can subscribe to the magazine here.