Same old keynotes not working? Experts reveal how to resonate with today’s attendees

The keynote has changed forever—and that is good news for attendees and planners. The seeds of change that put the one-hour PowerPoint presentation delivered from on high on the endangered list were sown in 1984 by a virtual newcomer named Ted. But the forces that accelerated the decline had more to do with changing expectations, and a growing awareness of the importance of delivering information more effectively, than with an affinity for big red dots or small microphones.

So, what makes a great presentation today? You know it when you hear it, and every event requires a different response based on individual goals, but we asked the experts for guidelines that could help your next event go viral—or at least get a rousing round of applause.

The Secret to Behavioral Change

The next time you are drafting an agenda, ask yourself if your goals would really be met by the default hour-long presentation. Could the same thing be accomplished in a half-hour, or even 20 minutes? That is the question Jonathan Bradshaw, founder of Meetology Lab and a speaker on the science of improving people skills, poses when asked about new ways to deliver content at events.

He has a point. Most presentations are designed to do two things: Make people feel something and deliver expert knowledge—or some combination of these. However, the traditional format of the “expert” on a stage with the audience in rows of chairs in a darkened room is not necessarily conducive to either goal.

If the reason everyone is gathered is to “motivate” them, then an effective presentation must do more than just make them feel inspired, sad or hopeful. Those things are fleeting. Real behavioral change has to be accompanied by delivering tools that are often specific to individuals and difficult to deliver to a large audience. “We can only motivate ourselves,” Bradshaw says.

If the purpose of coming together is to learn something, the speaker-on-high model is also problematic because most people do not take notes, and they can’t ask questions if they don’t understand something. They also can’t add a point if they have something to contribute. Studies have shown most people won’t remember more than two things at the end of the hour. By the end of the cocktail hour, they recall even less.

The solution, Bradshaw suggests, is experiential presentations, similar to the intimate campfires organized at IMEX Frankfurt, where 20 to 30 people gathered for roughly a half-hour on specific topics (disclosure: Bradshaw was director of business development for IMEX for seven years and keynote for IMEX America’s Smart Monday in 2016). When people are contributing to a discussion and can participate, they are open to new ideas.

Alternatively, he has seen multiple keynotes give short presentations to large groups and then retire to smaller breakout sessions where the conversation is more interactive and individual needs can be addressed for real learning. “People are wired to want to participate,” Bradshaw says.

This shift from speaker to trainer means that instead of one person talking 100 percent of the time, attendees take the mic as much as 80 percent of the time.

Bradshaw also cautions against relying too much on technology to provide the input. While polls and apps can help make attendees part of the presentation, the logistics can distract from the live experience. “Why would we fly around the world, check into a hotel and join a group of people in a meeting room just to sit and look at our phones?” he asks.

The Set-Up

Whether a presentation ultimately works often depends more on what happens before the lights go on than during that 45 minutes. Jeff Davidson, a speaker with Breathing Space Institute, says the mark of good presenters is that they do their homework. Preprogram questionnaires asking attendees what they need information about can help to mold a relevant talk. “It demonstrates that they are serious about their work and take both your time and theirs seriously,” he says.

Similarly, inviting a speaker to arrive early—possibly for the opening reception the night before—to mingle with guests and get a feel for their mood and issues, can help personalize the presentation.

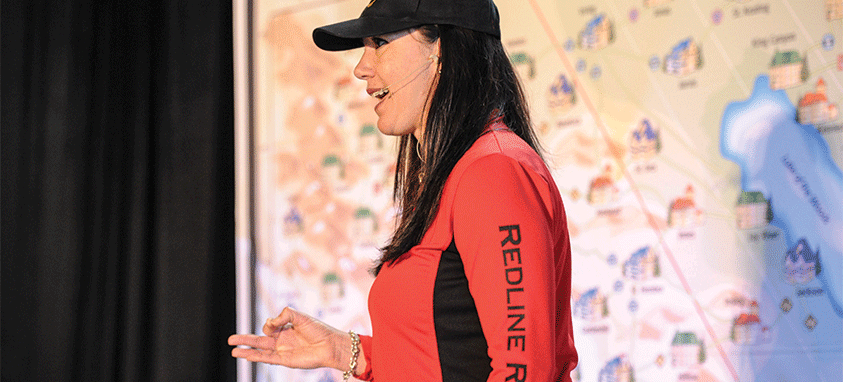

In today’s #MeToo world, it is also important to make sure your speaker meets your behavioral standards. Nancy Lauterbach, co-founder of Michigan-based RedPropeller Speakers Bureau, stresses the importance of doing due diligence on everything from accusations of sexual or other misconduct to inappropriate social media activity. She cites a recent search into the postings of a proposed speaker for a banking group that turned up comments inconsistent with the mission of the group. As a result, she contacted the manager to pull a contract that had been sent. “You really have to be careful today,” Lauterbach says.

Now for Something Completely New

Sue Wigston, chief operating officer of Eagle’s Flight, a consultant on using experiential learning to change behavior, suggests creating experiences that allow people to move around, interact, network or engage with others. “A shared experience will stick with them when they return to work,” she says.

Instead of directing the CEO—who may or may not be a natural-born speaker—to talk for an hour in a theater with revenue charts from the last five years, arrange breakout sessions led by the management team. “This step beyond the keynote could better optimize the investment in time and resources,” she suggests.

Wigston suggests trying something new or unexpected: “By doing something that may, at first, seem outside your company’s comfort zone, you may encourage attendees to reconsider their feelings and go along with what you have planned.” Consider it an opportunity to increase pre-event excitement and curiosity by promoting (or even hinting at) what you have in store for attendees when they arrive.

TED’s Recipe for a Resonating Idea

As you probably already know, TED (as in TED Talk) is not a person, but short for “technology, entertainment, design” and the 18-minute format leveraged the YouTube video platform to make ideas worth spreading accessible and convenient. Chris Anderson (pictured above), TED’s curator, says in his own TED Talk (3,782,030 views), that there is no formula for a great presentation, but there is a secret.

A good talk syncs the brains of speaker and audience, aligning millions of neurons to construct a shared idea. That linking of brainwaves can alter people’s operating systems, change world views and shape reactions. That is the power of an effective presentation.

But what are the ingredients that cause that chemical reaction?

Limited Scope: Focus the talk to one major theme. Ideas are complex, so limit the presentation to the single thing you are most passionate about and explain it properly with context and examples.

Empathy: Give listeners a reason to care. Before you can start building things inside the mind of your audience, you have to get their permission to welcome them in. Use curiosity and provocative questions to identify why something doesn’t make sense. Reveal a disconnect in their world view, and they will want to bridge that knowledge gap.

Plain Speak: Build your idea piece-by-piece out of concepts and language your audience already understands. Metaphors can play a crucial role in revealing how pieces go together. Paint a vivid picture to deliver a satisfying “aha” moment.