Does it really matter what flag a hotel flies?

Once upon a time, when you booked a hotel for yourself or a group, you could be fairly sure that it was owned and operated by the company whose name was above the door. In those faraway days, there were no national, let alone international, hotel brands. Those days are long past.

To explain what happened, look to the Marriott example. The largest hotel company in the world began as a root beer stand in Washington, D.C., in 1927, and didn’t open its first hotel, Twin Bridges Motor Hotel in Arlington County, Virginia, until 1957. As the 21st century approached, it owned hundreds of properties—most of them meetings hotels and resorts—until there was a seminal fork in the road, in 1993. It split into two entities, Marriott International and Host Marriott Corporation.

Host Marriott became the real estate company. Today, it owns 93 luxury and upper-upscale hotels and resorts on three continents.

Marriott International became a hotel marketing, franchising and management company. It was out of the bricks-and-mortar business. As it acquired or launched new brands, it hung its various flags—a total of 30 to date—over the door, but the building was constructed, renovated and mortgaged by an investment group.

All the major hotel companies did the same thing, with few exceptions. MGM Resorts International, for example, still owns all its hotel, resort and casino properties.

Hotel franchising wasn’t exactly new. Kemmons Wilson had begun to do it decades earlier, when he created the Holiday Inn chain after he could not find reasonably priced, clean and comfortable motel rooms where his kids could stay at no additional charge during a family trip from Memphis, Tennessee, to Washington, D.C. Even earlier, seven motor court owners in Florida had banded together as Quality Courts United, the forerunner of Choice Hotels International, which now franchises more than 6,800 hotels.

What was new was the marketing might of the internet and hotel loyalty programs, which both began to proliferate in the 1980s. For the first time, leisure and business travelers were able to easily find and book hotels in any location—and were rewarded for brand loyalty. Make that hotel company loyalty, because Marriott, Hilton and the other big players quickly realized it made sense to offer rewards points across their suite of brands.

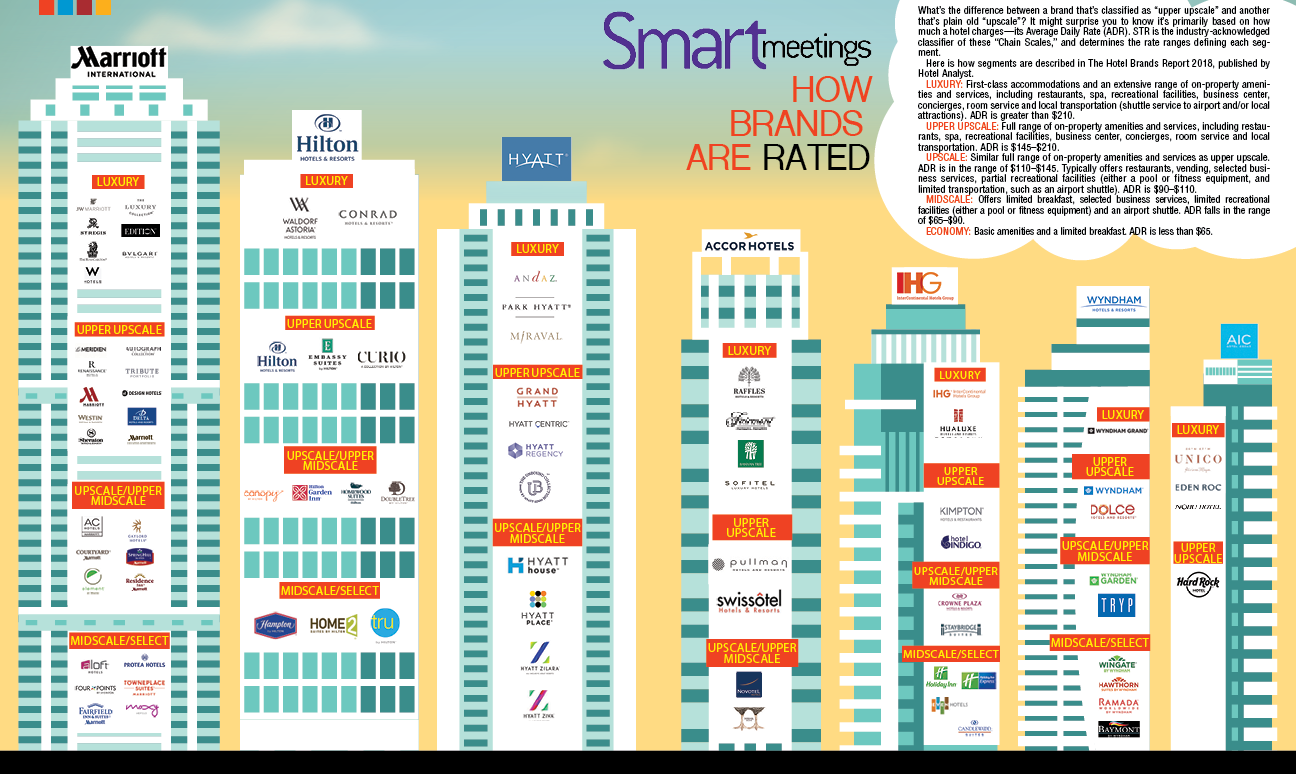

They also realized it made sense to own many brands. A bewildering number of brands.

Brand Degeneration

“If I’m supposed to be the expert, and I’m confused…,” jokes Jan Freitag, senior vice president of STR, a company based in Hendersonville, Tennessee, that tracks data in the global hotel industry. Freitag says the reason behind what he calls “brand degeneration” is that “the more brands you have, the more people you attract and the more power your loyalty program has.”

Multiple brands also enable more franchising. “If you have a Marriott downtown, and someone says, ‘I want to build another Marriott downtown,’ well, you can’t. It would violate the existing Marriott’s noncompete clause. But you could build a Westin. In other words, can you have too many brands? No,” Freitag says.

Nonetheless, brand experts say the psychology of hotel branding is shifting. The holy grail is still what researchers called “unaided recall”—do you know about this brand without any prompting? But dependability and trust used to be the most important brand attributes in the hotel world. They’re still important, but in this Instagram age, it’s just as important what checking into a particular hotel brand says about you. Because, chances are, all your friends and associates will immediately know all about it via social media.

Two phrases come up often in hotel brand conversations. Hotel company executives like to pour over their brands and survey attractive markets to look for “white space”—gaps in coverage or demographics being served. That’s the stuff of new franchising or branding opportunities. With nearly the entire last decade seeing unprecedented demand for hotel space and growth in hotel properties, there has been no lack of opportunity to sell more franchises and to create and expand brands.

The other is “swim lane”—as in, each brand should have a clear path (swim lane) to a specific demographic or psychographic audience; ideally, these lanes do not overlap. This became a challenge when Marriott’s existing 19 brands were joined by Starwood’s 11 brands. “Looking at some of Marriott’s brands side by side now, you see some that go away,” Mario Natarelli, a managing partner at brand intimacy agency MBLM who has worked as a branding strategist on several of the flags in the Marriott portfolio, told the website Bisnow. “I can imagine Aloft surviving, but I look at Moxy and others on the other side of the portfolio, and it’s a coin toss. It’s like if Chevy and Ford merged. Do you keep the F-150 or the Silverado?”

Aloft from Starwood and Marriott’s Moxy Hotels were head-to-head competitors for the millennial market, premerger. (Other observers also see brand confusion between Aloft and AC Hotels by Marriott.)

Marriott is keeping notably mum of the subject of swim-lane congestion, but while many industry experts expect the company to announce some repositionings or winnowing, Natarelli is among those who believe Marriott is well positioned for the future.

“I don’t think it matters in the short term whether you stay at a legacy Sheraton versus a Marriott; it’s all going into the same purse strings,” he says. “What we think is a bigger challenge is, as millennials become more of a dominant buying force and Generation Z moves in, how does this portfolio reflect the needs of those future travelers?”

Brands for the Future

That challenge, in part, explains why Sheraton, the third-largest of Marriott’s brands and a perennial meetings workhorse, is being relaunched with a design that is more millennial-friendly, with common workspaces, design-forward guest rooms and coffee bars that become cocktail spaces in the evening. As reported in Bisnow, Sheraton operators who opt out of the renovations are being told to reflag under a different Marriott brand or leave the company.

The push to appeal to younger travelers who prize a unique sense of place over dependable familiarity was also evidenced by the purchase of an 85 percent stake in Louisville, Kentucky-based 21c Museum Hotels in July by AccorHotels, which has 26 brands, including Raffles, Fairmont, Sofitel, Novotel and Pullman. Headquartered in Paris, the hotel group is the largest in the world outside of the United States.

What’s the bottom line for meeting planners amid the hotel brand explosion? Well, while planners are eager to meet attendees’ expectations for authentic, local experiences, it must be stated that many hip, design-forward lifestyle brands do not have ballrooms and have only limited meeting space.

And, as Freitag points out, nearly three-quarters of hotels built in the United States in recent years offer only select services.

“Group demand is growing,” he says, “but planner site selections may still turn out to be more about room availability and meeting space than brand.”

Soft Brands Explained

Autograph Collection by Marriott. Curio, A Collection by Hilton. Unbound Collection by Hyatt. We see these designations tacked onto hotel names as if they are specially curated groupings of the parent brand, but what are they really?

It’s almost easier to say what they aren’t. They aren’t owned (and, most likely, aren’t operated) by Marriott or Hyatt or whatever major brand is attached to the “collection.” They aren’t required to toe the line on the parent brand’s standards for design and amenities—in fact, no two of these properties are alike. They aren’t required to be much of anything except a credit to the major brand’s reputation and a contributor to its bottom line. (Curio owners, for example, reportedly pay a fee of 4 percent of gross room revenue, as do other Hilton franchisees.)

In return, they can leverage the power of the major brand in marketing, sales and loyalty program. And they help the parent brand satisfy the ever-expanding demand for bespoke properties that offer unique, authentic experiences.

The big hotel brands “took the heavy lifting of the brand standards out of the formula,” says Jan Freitag, senior vice president of STR.

Welcome to the world of “soft brands.”

A mere decade ago, they barely existed. In 2008, Choice Hotels International announced its Ascend Collection, a new industry concept that grouped “upscale independent, unique, boutique or historic properties with strong local brand equity that want to keep their own names and identities while tapping into a broader distribution channel.”

Today, almost all global hotel companies have soft brands, and some have more than one. According to STR, they will soon represent more than 1 percent of the total U.S. hotel-room inventory.

Here is a rundown, as compiled by STR.

Hilton Hotels & Resorts

- Curio, A Collection by Hilton: launched in 2014 as the company’s 11th brand; 55 properties, with a pipeline of 65.

- Tapestry Collection by Hilton: launched in 2017 to aggregate upscale properties; nine properties.

- Canopy by Hilton: launched in 2014 to offer boutique properties that are “locally inspired”; five hotels, with 16 more scheduled to open by 2021 in several countries.

Wyndham Hotels & Resorts

- The Trademark Hotel Collection: launched in 2017 as the company’s 19th brand, focused on “upper-midscale and above” hotels; 98 properties.

Marriott International

- Autograph Collection: launched in 2009 and focused on upper-upscale properties; more than 150 properties, with 77 in its pipeline.

- Tribute Portfolio: launched in 2015 by Starwood in North America and Europe; 29 properties, with 18 in its pipeline

- Luxury Collection: not a modern soft brand, but a group of hotels founded in Italy in 1906 and later acquired by Starwood; more than 100 hotels worldwide.

- Design Hotels: founded in 1993 by German hotelier Claus Sendlinger, a 74 percent equity interest was acquired by Starwood; nearly 300 unique hotels worldwide.

Hyatt Hotels Corporation

- Unbound Collection by Hyatt: launched in 2016 with the explanation that “unbound” meant it might include villas and other lodging alternatives; 13 hotels internationally.

Decoding Loyalty for Planners

Much ado has been made about Marriott International’s new loyalty rewards program, which rolled members of Starwood Preferred Guest and The Ritz-Carlton Rewards into one Marriott Rewards account across 29 Marriott-owned brands. Marriott Rewards itself will be rebranded in 2019, but the company is already leveraging the breadth of its 6,700 participating hotels by offering special promotions that dangle prizes such as bonus points and hotel nights.

Less attention has been paid to rewards programs aimed specifically at planners who bring groups to the major chains. These programs pay up to three rewards points per $1 spent. All have fine print that may cap rewards, but all are worth paying attention to as another way to trim expenses for future bookings, or to enjoy special perks.

Here is a recap of major meeting rewards programs.

Marriott Rewarding Events

Also newly updated, this program now awards planners two bonus points for every $1 spent at most Marriott brands (exceptions: Residence Inn, TownePlace Suites, Marriott Executive Apartments and Design Hotels). The number of points that can be claimed per event depends on your level of membership—a Platinum Premier Elite member is capped at 105,000 points, for instance, while a Silver Elite member can earn up to 66,000 points.

What counts toward bonus points? Spending on meeting space, guest rooms, food and beverage, audiovisual and other services supplied by the hotel. You must book at least 10 guest rooms for one night.

A nice feature when redeeming points is that donations to charitable causes are included. Or you can get credits toward future meetings, and personal perks, such as hotel nights (points needed are based on hotel category and peak or off-peak booking), vacation packages, cruises, air miles and gift cards.

Hilton Honors Event Planner Program

Unlike Marriott, any planner can earn up to 100,000 points per event at most Hilton brands—but you will get only a single point per $1 spent. There are no room or spending minimums, and points are earned only for booking guest rooms and meeting rooms.

For every 50,000 points, a $100 credit can be earned for a future event. Or points can be redeemed for personal stays, dining and experiences, as well as merchandise, charitable donations and more.

Be sure to have planner points stipulated in your contract, which must be booked through the participating hotel’s sales and catering department

World of Hyatt

Hyatt limits points earned per event to 50,000, at $1 per point. At least 10 guest rooms must be booked.

Redemptions yield $100 of meeting credit for every 7,500 points earned. Note that in addition to Hyatt brands, you can earn points from meetings at MGM Resorts International’s properties that participate in the M Life Rewards program.

IHG Business Rewards

IHG is the most generous in awarding points—three per $1 spent on guest rooms, meeting space and F&B, and up to 60,000 points per event (unless the specific hotel sets its own limit).

Points can be used for credits on future meetings and several other options, including digital downloads and office supplies.

Not all IHG properties participate in the program, but 4,600 do.

Wyndham Go Meet

A point is earned for every $1 spent, with no cap on the number of points that can be earned per event. A minimum of 10 guest rooms must be booked for at least one night.

Point redemption can be used for a future meeting, a charitable donation, personal travel, gift cards and other rewards. If redeemed for individual travel, any Wyndham property can be booked for 15,000 points per night.

Not every Wyndham hotel participates in the program, but several Caesars Entertainment properties do.

Omni Select Planner

Omni Hotels & Resorts recently launched a program that offers planners award and tier credits immediately upon signing a group or catering booking. Part of the company’s Select Guest loyalty program, it gives one award credit per $1,000 spent and one tier credit for each $10,000 booked.

Tiers are Gold Level (0–9 credits), Platinum Level (10–29 credits) and Black Level (more than 30 credits).

Twenty award credits can be redeemed for a free night at any of the 60 Omni luxury resorts or hotels across North America. Besides free room nights, planners can choose from locally inspired welcome amenities and experiences, flexible check-in and check-outs, and shoe shines and pressings.

The Birth of Boutique

So-called boutique hotels were originally, by definition, independent and unbranded. Today, many are neither unbranded nor truly independent. Yet now hotels in this category have advantages pioneers in the boutique hotelscape did not. A cool website, savvy social media and online booking engines can attract a steady stream of travelers—and planners—who might not have even realized that these unique, idiosyncratic properties existed before the internet.

And that’s why it is even more extraordinary that, way back in the 1980s, two men successfully launched North America’s first boutique hotel brands in the same city. That city was San Francisco. The men were Bill Kimpton and Chip Conley.

In 1981, 45-year-old Kimpton, an investment banker who started out as a typewriter salesman for IBM, opened Bedford Hotel. He continued converting old hotels or buildings into one-of-a-kind, distinctive properties until Kimpton Hotels & Restaurants was acquired by InterContinental Hotels Group in 2015 for $430 million.

Kimpton said in interviews that he had found his calling as a young boy, playing Monopoly with friends. His passion was collecting hotels.

In 1987, Conley, a 26-year-old Stanford University business grad, bought a seedy, 44-room motel in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district and made it into a hotel that eventually spawned a family of more than 90 boutique properties in eight countries, with approximately $2 billion in revenues. Conley’s original property, aptly named The Phoenix, was niche-marketed as “irreverent, adventurous, funky, cool and young at heart” to touring rock bands, musicians and hip filmmakers.

Conley’s brand, Joie de Vivre, is today part of Two Roads Hospitality, founded by Hyatt Hotels heir John A. Pritzker and acquired in October by Hyatt Hotels Corporation.

Conley is better known these days for his work with Airbnb, where he is the company’s strategic advisor for hospitality and leadership.